Visitors to the Salton Sea have, until recently, had the opportunity to see more than two hundred species of birds. But one bird that is most frequently associated with California’s largest inland lake is the Eared Grebe, a popular waterbird that moves throughout vast portions of the American West during the year, taking advantage of inland saline lakes like the Salton Sea. The reason the Eared Grebe is particularly associated with the Salton Sea is that historically it has been assumed that up to 90 percent of all Eared Grebes use the Salton Sea at some point during the year. In other words, the Salton Sea is a sort of funnel for the birds as they move throughout their range

But in recent years, due to ecological conditions that have almost completely eliminated the birds’ source of food, sightings of Eared Grebes at the Salton Sea have plummeted. And this prompts the questions of where are they going instead, and what effect is this having on their health?

Eared Grebes breed in northwestern and midcontinental North America during late spring and summer months. They begin their southern migration late in the summer and almost the entire population stages during the fall months in the Great Salt Lake and Mono Lake to forage and molt before heading to their wintering grounds that include coastal California, the Salton Sea and coastal Mexico. Eared Grebes are considered abundant but are also vulnerable because large portions of the population depend on a few major saline lakes during key portions of their migration. Lakes like the Great Salt Lake, Mono Lake and the Salton Sea play important roles in the life history of this species.

In recent years, during fall staging, more than 5 million Eared Grebes have been counted at Great Salt Lake, and more than 1 million have been counted at Mono Lake. At Salton Sea, where birds either spend the winter or appear during late winter or early spring, estimates in the past have suggested upwards of 90 percent of the North American population pass through Salton Sea in some years.

During 1999 surveys, there were an estimated 434,000 to 583,000 in November and December (Shuford et al 2000). While in earlier years, Eared Grebe population reached and estimated 3.5 million birds (Shuford et al 2000). While there is no consistency or regularity in surveying birds at the Salton Sea by survey type or date, these numbers, along with the data we present below, all suggest that while tremendous portions of the Eared Grebe population formerly utilized the Salton Sea during winter or spring, that is no longer the case.

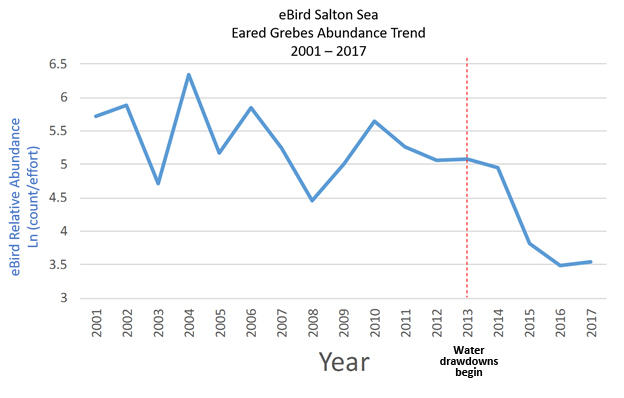

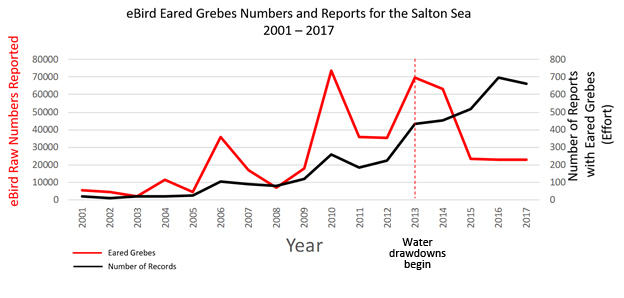

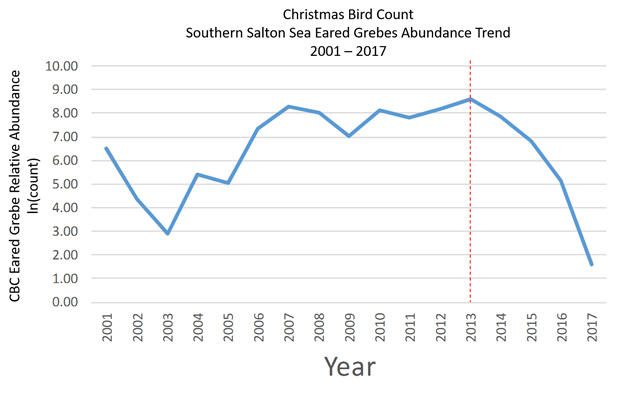

Biologists have been hearing anecdotally about alarming declines in recent years in the numbers of Eared Grebes at Salton Sea during winter and early spring, and our own surveys conducted every other month for the past year-and-a-half indicate a decline of upwards of 99 percent decrease during fall and winter months. While our surveys do not count the entire Sea, at our 14 counting stations positioned around the entire Sea, we counted only three Eared Grebes in the fall and winter of 2017-2018. We therefore decided to look into community science sources of data to see if other data sources were showing similar results. Although the Christmas Bird Count and eBird abundance data for Eared Grebes do vary through time around the Salton Sea it appears that there has been a decline trend that may have begun after 2013.

eBird data indicates declines beginning in 2013. Although there has been a large increase in the number of people reporting Eared Grebes, total numbers of reported Eared Grebes has declined since that time. In other words, many more people are looking for these birds but are seeing fewer of them.

Audubon’s Christmas Bird Count (CBC) data shows similar and corroborating trends. There has been a decrease in numbers of Eared Grebes reported in both CBC surveys that are conducted around the Salton Sea (northern Salton Sea and southern Salton Sea). These data also show variation in number over time but there is a clear trend of decreasing numbers beginning around 2013. For example in the southern Salton Sea CBC survey there are often numbers reported in the many thousands. These have steadily declined to only five Eared Grebes being reported in the 2017 survey.

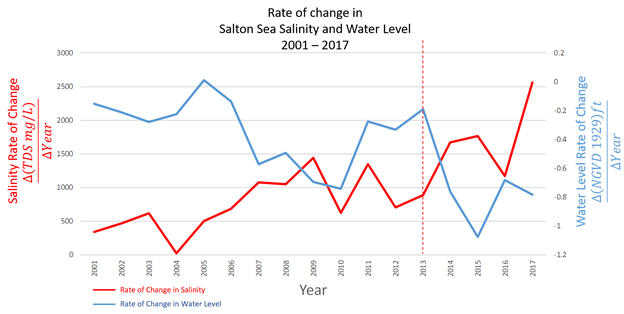

It is important to note that water drawdowns began to increase in 2013 as well. The rate of decrease in the water level of the Salton Sea increased by 296 percent between 2013 and 2014. The salinity of the sea is increasing with this decreasing water level. Between 2013 and 2014 the rate of increase in salinity increased by 88 percent. While the sea has been shrinking and becoming saltier for some time, this is a rapid increase in the rate at which it is happening. These changes not only change the habitat that birds depend on, but the salinity changes have a negative impact on food sources for birds including fish species and likely pile worms, a major source of food for Eared Grebes at the Salton Sea.

The Eared Grebe trend we are seeing at the Salton Sea does not appear to be happening across the species range, but data do show a significant decline in the populations of Eared Grebes in Central and Southern California. The trends indicate that changes at the Salton Sea are likely impacting Eared Grebes at the Sea, but we don’t know how that may impact the Eared Grebe population as a whole. These are migrating birds and they may be using alternate foraging grounds to compensate for lost habitat and foraging grounds at the Salton Sea. For instance, this winter had an uptick in numbers in places like Mono Lake and San Diego Bay. Being that the decline of Eared Grebes at the Salton Sea only really began in earnest in 2013, it may be too soon to tell if removing the Salton Sea from the birds’ migratory journey will impact these birds, which can live to be 10-15 years old.

Dan Orr is a spatial & GIS ecologist for Audubon California.

By Dan Orr

A New Colony of Caspian Tern Decoys on Aramburu Island

Richardson Bay Audubon Center is attacting breeding pairs of Caspian Terns with these newly painted tern decoys—a strategy successfully used by previous tern relocation efforts.