Sandhill Crane

Latin: Antigone canadensis

A new model for conservation.

Sandhill Cranes Photo: Choktai Leangsuksun

California’s public lands play a vital role in the success and survival of millions of migratory birds. As birds make their perilous journeys across the Pacific Flyway, they need safe and reliable places to rest and eat. These protected lands provide access to food, water, and nesting habitat needed to sustain them along the way.

There are 34 National Wildlife Refuges in California that play a key role in supporting migratory birds. The Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge is one of the most important places for birds in North America, offering a rare spot for shorebirds to stop as they travel over large stretches of dry land.

Mono Lake and its surrounding ecosystem provide a diverse landscape, from marsh and meadow to sagebrush steppe and forest. It is ideal habitat for migrating birds, mule deer, and other big game species. In southern California, the Mojave Trails National Preserve and Joshua Tree National Park provide critical habitat for species such as the Burrowing Owl, Red-tailed Hawk, and Prairie Falcon.

So what do these regions have in common? They are all part of a network of large public lands corridors providing essential habitat along migratory flyways. When public lands are well-managed and kept healthy for migratory birds and other wildlife, they provide many benefits for people, such as clean air and water, economic opportunity, recreation, hunting, mental and physical health benefits. Plus, these intact lands buffer against the effects of climate change.

Right now, California is poised to be a national leader in public lands conservation, working at the intersection of climate change, energy production, land management, and wildlife conservation. Visit the StoryMap to see how.

Black-necked Stilt Photo: Logan Southall

Explore our new StoryMap, which identifies key migratory pathways and highlights the most important public lands in California for birds.

California is first in nation to commit to protecting 30% of our lands and waters by 2030.

By partnering with landowners, we can create lasting protections for birds.

Conservation ranching techniques create habitat and sequester carbon. Under a new bill, the state would pay ranchers to implement them.

Vital protections are needed for wetlands that depend on groundwater under the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act

Coalition of conservation and community groups says groundbreaking is positive step towards ending years of inaction at California’s largest lake.

Audubon science finds that two-thirds of North American birds are at risk of extinction from climate change.

Conservation groups including Audubon California hope that more than $80 million included in the recently-approved state budget will be the first step in a longer, more substantial commitment from the Legislature to addressing the developing environmental crisis at the Salton Sea. The $80.5 million for planning and restoration at the Salton Sea, part of the $167 billion state budget, will ultimately come from Proposition 1 funds approved by voters in 2014.

While the new funding marks the largest amount that the State of California has ever contributed to restoration at the Salton Sea, it is nonetheless only a fraction of the several billion dollars that will be needed to stabilize the situation there.

The funding will help the state pay for the development of a long-term management plan that seeks to address the problems created by reduced water deliveries to California’s largest inland lake. As the Salton Sea shrinks in the coming years, it is expected to have serious ramifications for the more the 400 species of birds that rely on its habitat. Less water will also result in the exposure of hundreds of acres of plays, creating a toxic dust and a serious public health hazard.

Money will also jump-start restoration of habitat along the edge of the lake, creating infrastructure to move water to a number of habitat areas.

An independent California oversight agency last week called on California Gov. Jerry Brown to declare a state of emergency to resolve the environmental disaster unfolding at the Salton Sea. In a strongly-worded letter, the state’s Little Hoover Commission shared the results of recent hearings, arguing that the Salton Sea should be given as high a priority as high speed rail, the twin tunnels, reduced carbon emissions, and increased renewable energy.

The Commission is responding to the upcoming implementation of water diversions from the Salton Sea that will eventually result in 40 percent less water filling the state’s largest inland lake. This will have a devastating impact on bird habitat and expose huge swaths of lakebed, potentially creating dust that will present a serious public health threat to the 650,000 Imperial County residents nearby.

Audubon California is particularly concerned about the situation at the Salton Sea because of the regions particularly high value to birds. More than 400 species use the Salton Sea, many of which are threatened or endangered species.

“Unlike a wildfire burning out of control or an oil spill blackening beaches, the Salton Sea disaster is slowly unfolding, and has been all but ignored until recently,” the letter reads. “When other disasters destroy California lives and livelihoods, Governors declare a state of emergency. The looming Salton Sea disaster warrants the same level of urgency.”

The commission offered four specific recommendations to get the state’s response to this crisis moving.

A picture says a thousand words, as the saying goes. The above postcard from the 1950s shows a bustling Salton Sea Marina, a center of fun and recreation.San Bernardino Valley Audubon's Drew Feldman recently visited the exact same location and took the photo below, which shows just how much things have changed over the years.

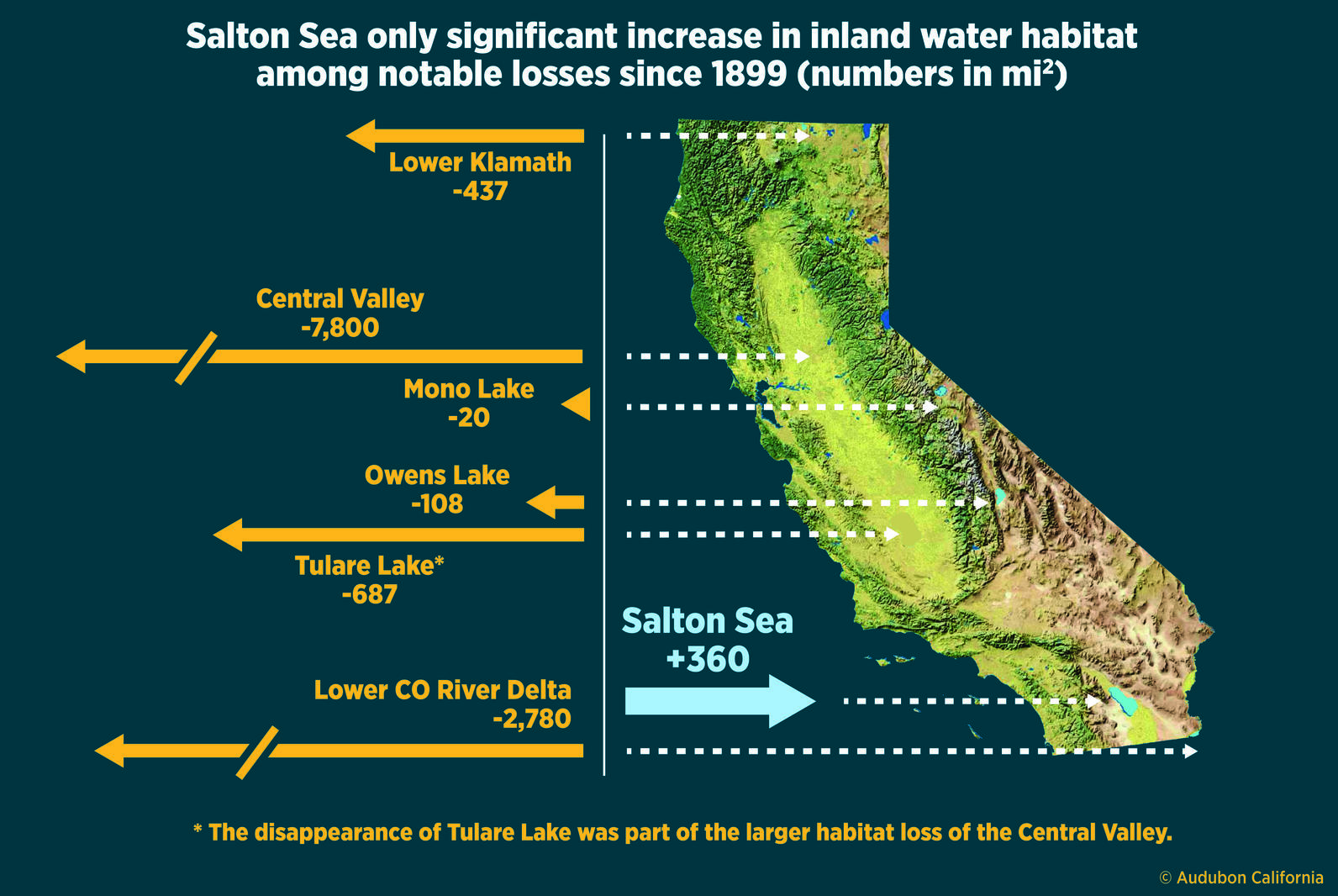

Audubon California Executive Director Brigid McCormack today writes in the Desert Sun that while the narrative around the Salton Sea is often one of environmental decay, the site remains one of the most important places for birds on the Pacific Flyway. She notes that it was created at a time when humans were wiping out natural inland water habitat:

"For birds, the creation of the Salton Sea came at just the right time – just as humans began wiping out wetland habitat throughout California.

Two years before dredging began on the Imperial Valley canal, the last remnants of Tulare Lake disappeared. Once the largest freshwater lake in the West, Tulare Lake was nearly twice the size of the Salton Sea, and anchored more than five million acres of Central Valley wetlands, 95 percent of which are now gone.

In 1906, the federal government began work on the Klamath Project, which eventually eliminated 437 square miles (80 percent) of wetland habitat in the Klamath Basin along the California/Oregon border.

Just a few years later, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power began diverting water from the 108-square-mile Owens Lake, where Native Americans recalled a sky blackened with migratory birds, and naturalist Joseph Grinnell found great numbers of avocets, phalaropes and ducks. By 1926, Owens Lake was gone.

Fascinating piece today in the Los Angeles Times about the growing concern over declining water levels in Lake Mead that, if they continue to fall, could trigger substantial water cuts in Arizona and New Mexico. Because of this pressure is growing on California users to reduce its use of Colorado River Water. You might recall recently that the Imperial Irrigation District, one of the primary users of water from the Colorado River, has said that will be uncomfortable with any agreement regarding Colorado River water unless the major issues of habitat conservation and dust mitigation at the Salton Sea are resolved.

"All the parties are under pressure to reach an agreement by the end of this year, before the current administration leaves office and the process has to start anew with new federal overseers. But the interstate complexities may pale in comparison with the difficulty of working out agreements among water users within each state. California's Imperial Irrigation District, which has the largest entitlement of Colorado River water, has balked at any agreement to preserve water levels in Lake Mead without a parallel agreement to preserve the Salton Sea. That huge inland pond has suffered as a result of earlier multi-billion-dollar deals by which the Imperial Irrigation District transferred water to San Diego, the MWD and other users.

The shrinkage of the sea already is an environmental and public health disaster. Withholding more water in Lake Mead without a rescue plan would be unacceptable, Imperial Irrigation District General Manager Kevin Kelley said recently. "The Salton Sea has always been the elephant in the room in these talks," he told the Desert Sun newspaper."

When Audubon California talks about the Salton Sea, we often highlight that about 400 species of birds make regular use of this habitat -- massive numbers of sandpipers migrating between Alaska and South America, as much as 90 percent of the world’s Eared Grebes, and large numbers of American White Pelicans, Double-crested Cormorants, the threatened Snowy Plover. Without the Salton Sea, these species and many others would struggle for survival.

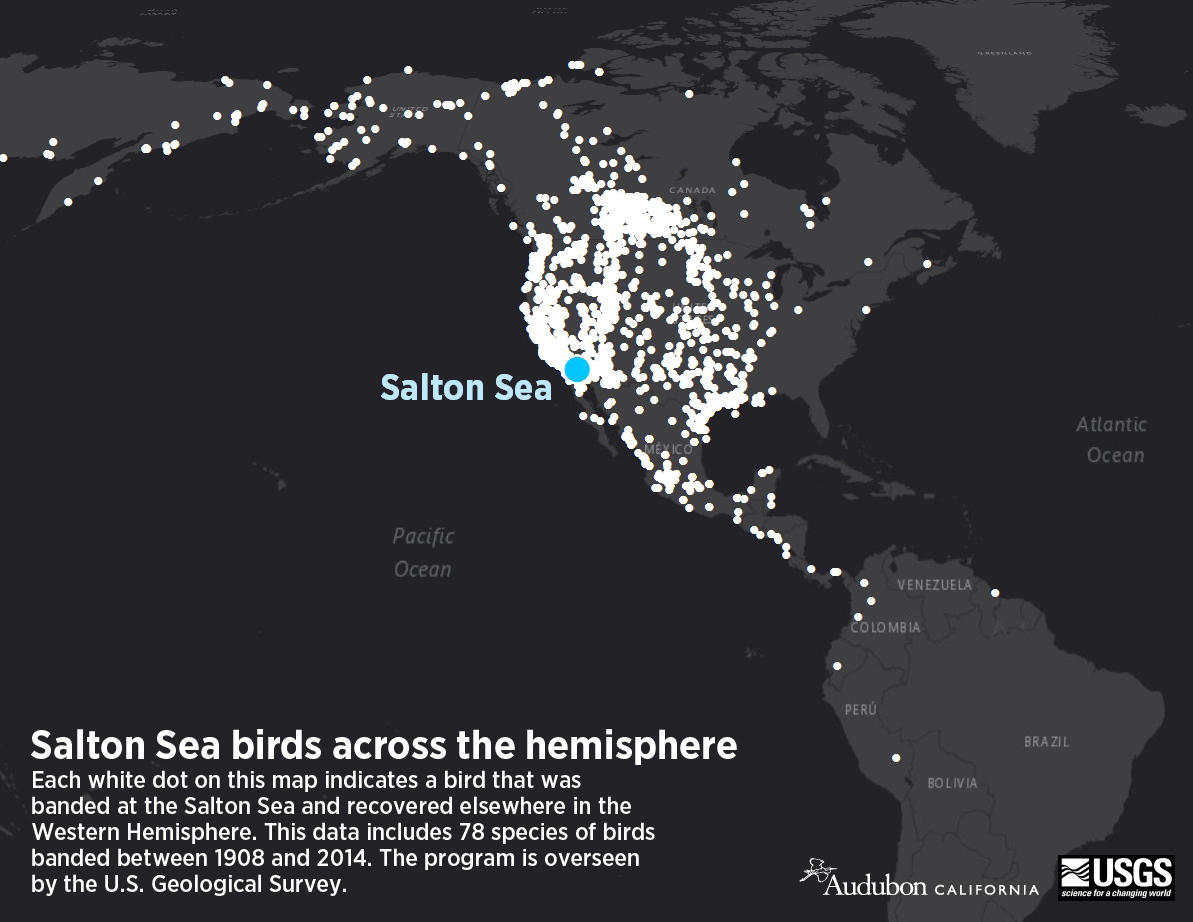

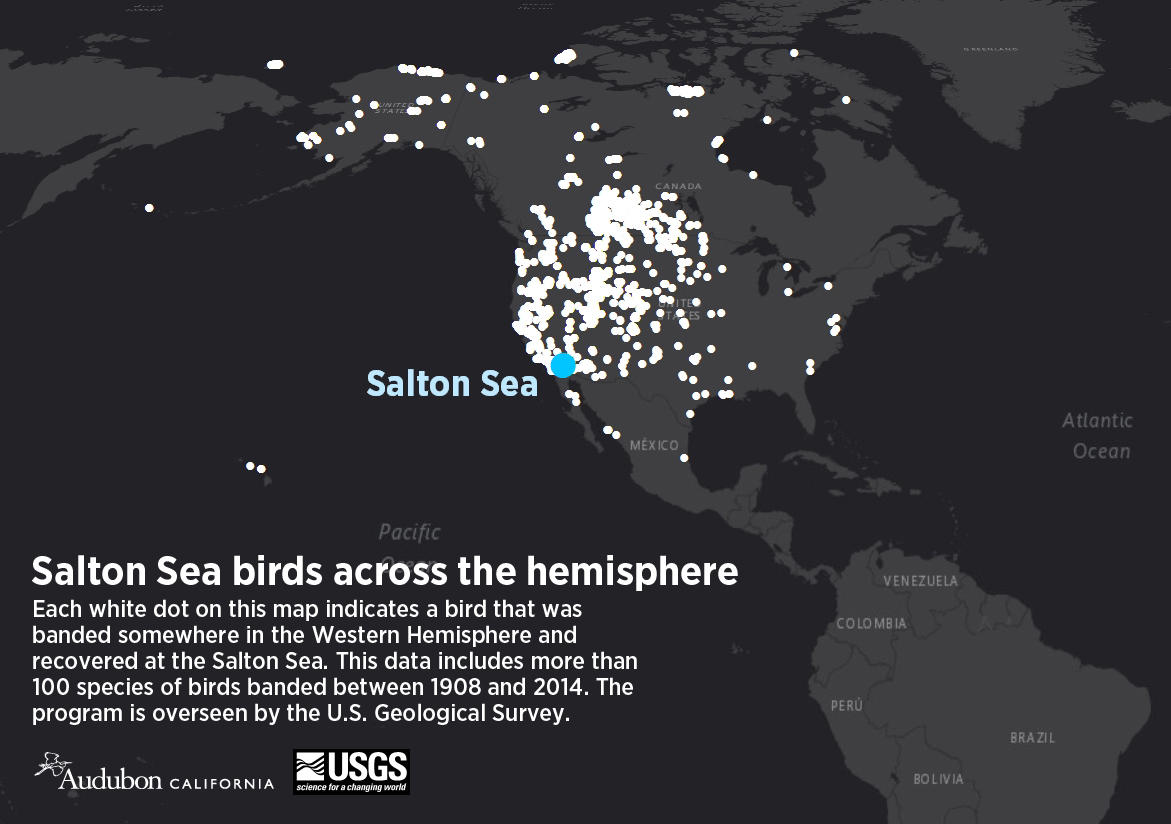

The two maps below offer another view of how birds from all over the Western Hemisphere use the Salton Sea. Since 1908, volunteers and researchers have been banding birds for the U.S. Geological Survey's North American Bird Banding Program, and so we have data on where we found birds that were banded at the Salton Sea, as well as where birds were banded that ultimately turned up at the Salton Sea.

Birds banded at the Salton Sea and found elsewhere

Birds banded throughout the Western Hemisphere and found at the Salton Sea

With news that representatives of California, Arizona, and Nevada are negotiating potential cutbacks to relieve water usage from the overtaxed Colorado River, the water district holding the largest rights to Colorado River water said that issues at the Salton Sea need to be resolved before any settlement regarding the Colorado River.

Our newsletter is fun way to get our latest stories and important conservation updates from across the state.

Help secure the future for birds at risk from climate change, habitat loss and other threats. Your support will power our science, education, advocacy and on-the-ground conservation efforts.

California is a global biodiversity hotspots, with one of the greatest concentrations of living species on Earth.