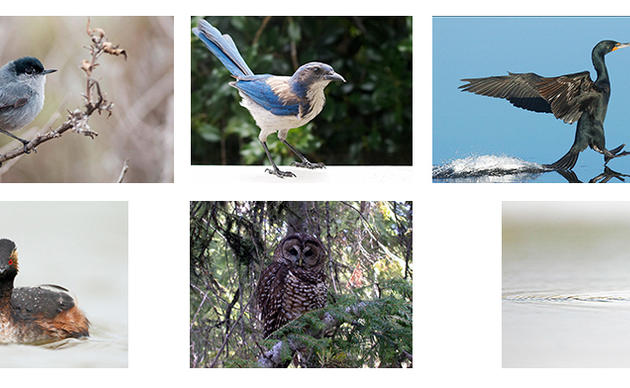

Your 2016 Bird of the Year nominees

Cast your vote now for the 2016 Bird of the Year

California Scrub Jay

Technically, 2016 marks the first year of this species’ existence. Ornithologists determined that scrub jays found along the California coast are different from the jays found in the eastern part of the state – so much so as to require a new species. The coast jays will have the honor of keeping the original, scientific name of the Western Scrub Jay, which is California Scrub Jay.

The decision was published in American Ornithologists' Union's Checklist of North American Birds. A resource that the union produces every year and acts as the de facto authority for North American birds.

Committed birders have long noticed the difference between inland and coastal scrub jays. Jays found on the coast have a more saturated hue and bigger bills.

California Scrub Jays are a divisive bird – while some are bewitched by its showy, noisy attitude, others find the corvid to be too bossy and aggressive. It’s a common bird to see near picnicking areas, campgrounds, and anywhere it thinks it may find a peanut.

Coastal California Gnatcatcher

A group of southern California developers attempted to delist the Coastal California Gnatcatcher in 2015 by claiming it wasn’t a unique subspecies. Fortunately, this year the US Fish and Wildlife Service denied the group’s request after thousands of Audubon members, renowned scientists, and bird lovers wrote letters in support of the original listing and debunking the developer’s claims.

The California Gnatcatcher was designated as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 1993, after an extensive review by federal agencies determined that the rapid loss of coastal sage scrub habitat made the bird worthy of protected status. Coastal sage scrub habitat is particularly in high demand for development, as it tends to occur in low-lying areas close to the ocean. It remains one of the most endangered habitat types in North America.

The California Gnatcatcher is a small blue-gray songbird with dark blue-gray feathers on its back and grayish-white feathers on its underside. Its long tail is black with white outer tail feathers. Since the 1980s, at least, experts have considered the California Gnatcatcher rare. A survey conducted at the time of its listing in 1993 estimated the number of California Gnatcatcher pairs in the Golden State at about 2,500, although there is reason to believe that numbers could have been higher. The coastal sage scrub habitat the bird depends on has been in rapid decline for decades, due both to development and habitat conversion caused by repeated, intense fires. Some researchers estimate that as little as 10 percent of California’s original coastal sage scrub habitat remains today.

Audubon California’s concerns for the conservation of the Coastal California Gnatcatcher are both local and regional. Starr Ranch Sanctuary is a 4,000-acre preserve owned and operated by Audubon in the foothills of the Santa Ana Mountains in southeastern Orange County, California. Point count surveys started in 2011 in coastal sage scrub habitat have located 10 possible territories so far and we expect more territories as trained citizen science volunteers continue to survey every spring.

Double-crested Cormorant

The Double-crested Cormorant made national headlines this year after a federal district court ruled that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers acted unlawfully by failing to consider alternatives to killing double-crested cormorants on the Columbia River in Oregon. The Audubon Society of Portland was instrumental in advocating on behalf of the slaughtered birds.

The Double-crested is the most distributed cormorant in North America, and the only one likely to be seen inland. Inky black in color with glorious deep-blue eyes, the cormorant’s beauty sneaks up on you. It has a long body that is perfectly engineered for diving, which is why it can found near lakes, ponds, and coastlines. The adaptable bird can make any aquatic habitat suit its needs as it eats everything from fish to frogs – anything it can spear with its hooked beak.

In addition to the Columbia River, Audubon has been working to protect this bird’s colony at the Salton Sea, which has been made even more critical after the Army Corps culling in Oregon.

Eared Grebe

2016 marked several milestones for Audubon’s work for the Salton Sea including the commitment of $80 million by the state of California for restoration efforts. The sea is a globally significant Important Bird Area. For more than a century, the sea has served as a major nesting, wintering, and stopover site for millions of birds of more than 400 species. Today, Eared Grebes feed at the Sea in late winter by the hundreds of thousands in rafts far out on its surface.

For years, irrigation run-off water in the Imperial Valley fed the Salton Sea. But in 2003, a deal was struck to divert more than 400,000 acre-feet of water that once flowed to the Salton Sea to San Diego and Coachella for urban uses. In 2018, water provided to the Salton Sea as mitigation for the 2003 deal will be shut off, meaning the sea will shrink even further, troubling news for the tiny Eared Grebe. Audubon California is addressing some of the immense challenges of the Salton Sea through a three-pronged approach: habitat mapping, public engagement, and through policy.

With its golden tufts of plumage rising from the sides of its head and its striking crimson eyes, the Eared Grebe already stands out from the crowd, but witnessing their mating ritual on their breeding grounds in wetlands to the north elevates the experience of spotting this waterbird to a whole other level. Pairs will swim side by side, turning their heads and calling loudly. This is followed by the male and female simultaneously rising up, out of the water into a rush across the water.

Northern Spotted Owl

The Northern Spotted Owl has inhabited the old-growth forests of the Pacific Northwest for thousands of years, but its population has suffered in modern times. First impacted by the logging industry, the owl earned “threatened” designation under the Federal Endangered Species Act in 1990. Despite the federal listing, the bird continues to decline rapidly due to habitat loss, encroachment by other species, climate change, wildfire, and other factors.

Northern Spotted Owl numbers are dropping throughout their range, and in some cases, those declines are accelerating. According to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, the species is estimated to have declined by nearly 4% a year since 1985. In California, some of these losses have been severe, which why Audubon and our members this year successfully supported Environmental Protection Information Center in their petition to list the species under the California Endangered Species Act.

The new state listing will result in greater scrutiny of logging, forest management, and development within the bird’s range increased coordination among public agencies, and the likelihood of additional funding for protection and recovery efforts. There are also efforts by other conservation groups to add the California Spotted Owl to the state endangered species list.

While the fight for the owl’s future has been fierce, the raptor looks anything but with its round dark eyes and rounded features and unlike other species won’t startle upon approach. The bird has a deep hooting call that echoes romantically through old growth forests of Northern California. Mated pairs have high site fidelity and nest in cavities deep in trees, cliff sides or caves. True to its name, the owl has white spots that cover its body.

Western Sandpiper

Over 200 bird species in California depend on agricultural habitats for at least part of their annual life cycle, and this includes the Western Sandpiper. Audubon California continued working with private landowners in 2016 to modify land management practices to benefit birds as well as continuing to advocate for the restoration of saline lakes.

We’ve partnered with the Natural Resources Conservation Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to protect and implement habitat enhancement projects permanently. Our programs are valued as replicable models that can be copied throughout the US. Audubon biologists have published papers alongside our partners to make this information readily available. Along with our efforts in the Central Valley, Audubon has created habitat modeling that will help save sandpipers from the effects of climate change and sea level rise.

The Western Sandpiper is the second smallest of all the sandpipers found in California. It has brindled wing feathers and a speckled white belly. During breeding season, the bird will appear a redder hue. It has a bill of medium length that it plunges into mudflats in pursuit of food.

How you can help, right now

Get Audubon CA in Your Inbox

Our newsletter is fun way to get our latest stories and important conservation updates from across the state.

Donate to Audubon

Help secure the future for birds at risk from climate change, habitat loss and other threats. Your support will power our science, education, advocacy and on-the-ground conservation efforts.

HOTSPOT: Flyover of California's Birds and Biodiversity

California is a global biodiversity hotspots, with one of the greatest concentrations of living species on Earth.