Plumas Grebe Festival, Chester, CA August 18-20, 2017 - dispatch from Maren Smith, Mt. Diablo Audubon board member and newsletter editor

Anxious to see the nesting rafts of the Western and Clark’s Grebes on Lake Almanor, one of the largest breeding populations in California, and hopeful of witnessing the spectacular mating “dance”, we headed to Chester, CA, about a 4.5 hour drive from the Bay Area to partake in the 2nd Annual Plumas Audubon Grebe Festival.

The festival included 42 activities for a nominal fee from hikes to kayaking and everything in between. They also offered free events, a children’s art contest with adorable entries displayed in the lobby, vendors, as well as some kids’ games including a grebe race on a downhill track and a “ring the grebe” game.

It was well worth the long drive as we got to see four different grebe species, as well as a pair of migrant Red-necked Phalaropes. By the end of the trip, I could confidently tell the difference between the two main species, the Western with the black color extending below the piercing red eye, like a Western bandit from an old cowboy movie, and the Clark’s black crown stopping just short of its red eye. In addition, the sharp beak of the Western Grebe is yellowish-green, while the Clark’s is a bright yellow-orange color.

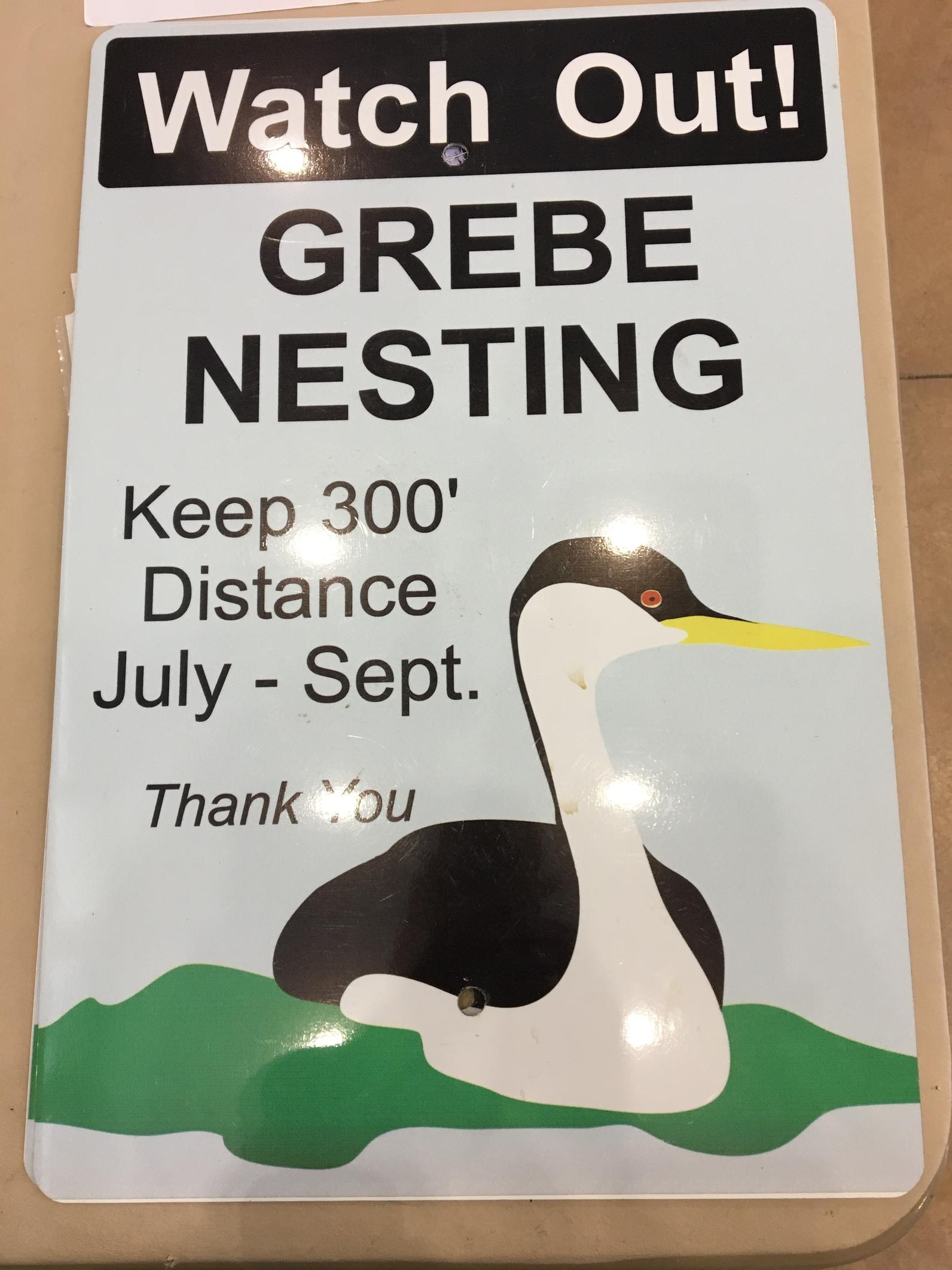

Signs close to the colonies and at boat launch areas warn people to keep a safe distance from the grebes.

Grebes are late nesters, nesting on Lake Almanor from June-September. The 2-4 (on average) bluish eggs become stained brown from plant matter over the course of 23 days. Upon hatching, the young climb aboard their parent's back, finding a warm spot beneath the feathers, called “back brooding”. After a few weeks, the young attempt to crawl back up on their parents back. We got a chuckle out of watching the mother kick out as if to say, you are just too big for that nonsense, kiddo.

The depth of the water is critical, not only for availability of fish for food and for plant material for nests, but to prevent predation by land mammals. In addition, if the water level dips too high or too low, the grebes may abandon the nest.

Lake Almanor is a man-made reservoir in Plumas County, just south of Mt. Lassen. With a maximum depth of about 90 feet, it is flush with fish, a grebes favorite meal. It is a hot spot for human recreation as well as a breeding colony for the 35% of the grebes in California, and a nesting site for Bald Eagles, Osprey, and many other fish-eating birds. Surveys by Plumas Audubon estimate over 3000 grebes on Lake Almanor this year.

Reservoir management is critical for the migrating nesting grebes who depend upon the aquatic vegetation to build their nests, and the water level at an acceptable level to build their rafts near enough land to get the material, but far enough out to avoid land predators.

During the drought, water was at a premium, so it was released from the reservoir to thirsty crops and humans, but it was a disaster for nesting grebes that suffered low numbers of chicks hatched. This is an ongoing concern.

Nesting surveys done by Plumas Audubon in conjunction with Audubon California count the birds to provide data to inform PG&E of reservoir management practices that will benefit both humans and birds. There is a direct link between water levels in the lake and nesting success. In 2015, at the drought peak, only one chick survived for every three adults.

Though the species is not listed as endangered, the drop in reproduction could become a conservation disaster. Appropriate management of water levels on Lake Almanor could help avoid a potential catastrophe.

As our boat guide drove us all around the lake, though we watched and waited, we did not observe the courtship display that begins with the male and female grebe presenting a piece of slimy plant material to the potential mate in what is termed the “weed ceremony”. Nor did we get to witness the showy “rushing dance” where the mated pair dip and bob their heads in unison before they “run” at a full sprint across the water before diving headfirst into the water in tandem.

However, we were lucky to hear the persistent begging calls of the young, the subsequent dive by their parents, and the presentation of a fish to a hungry, young grebe. The young Western Grebes are mostly gray, while the Clark’s are a downy white color. We were treated to views of young grebes riding on their parent’s backs that more than made up for the absence of the dance party on the lake.

Soon, the grebes will return to the Pacific Ocean with their young. We were fortunate to have this close-up view of such elegant and fascinating birds, and are already plotting our return trip to this scenic area.

For more detailed information about the Plumas Audubon Grebe pilot project go to plumasaudubon.org.

Monthly Giving

Our monthly giving program offers the peace of mind that you’re doing your part every day.