Two weeks ago, I went on my first pelagic birding boat trip off the central coast of California. It was foggy, it was 10 hours, and it was glorious. While we were out in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, I witnessed the breaching of the endangered fin whale (second largest whale on the planet), was overjoyed by the playfulness of thousands of dolphins jumping and diving in every direction, and of course, admired and misidentified all the seabirds that graced me with their presence. I got several lifers that day, but two species stood out – the Sooty and Pink-footed shearwaters. While they might not be as flashy as a Rhinoceros Auklet or a Sabine’s Gull (which we also saw), these two species have been on my mind as they have significant populations within the boundaries of the newly designated Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary, an effort Audubon, Morro Coast Audubon, and over 18,000 Audubon members have been supporting since it was nominated by the Northern Chumash Tribal Council.

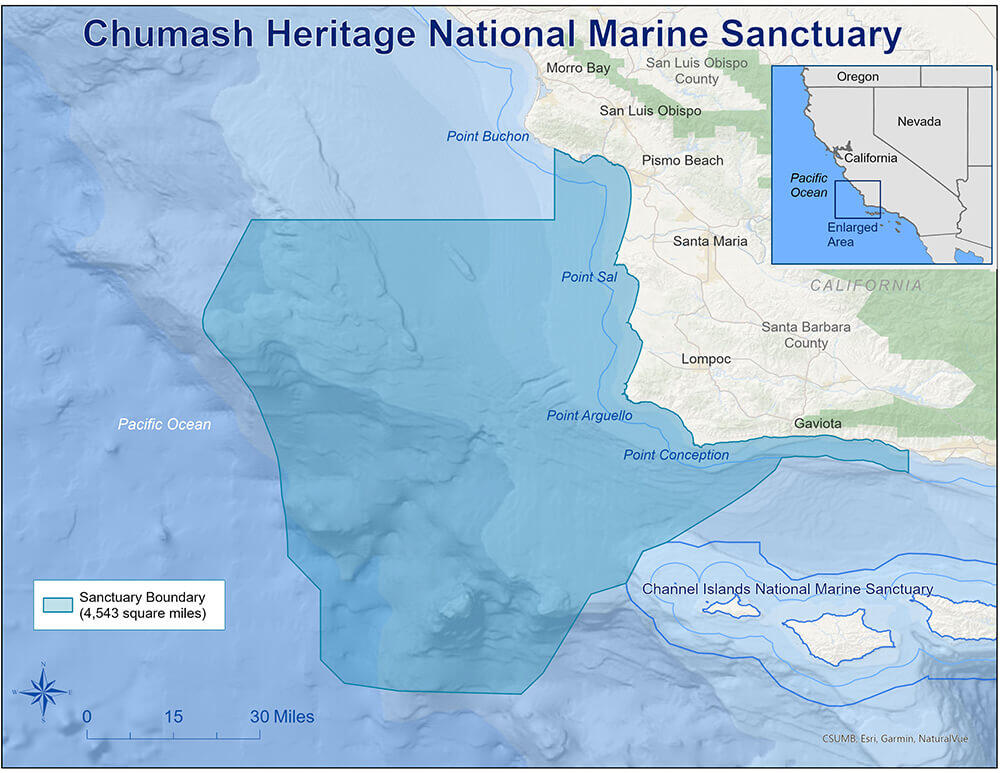

The sanctuary is located along California’s Central Coast between the existing Monterey Bay and Channel Islands national marine sanctuaries. It is the first new sanctuary designated in California in over 25 years and is the third-largest national marine sanctuary in the U.S. As the first Tribally-nominated Sanctuary, the designation is historic, and protects over 4,500 square miles of vital marine and cultural resources. National marine sanctuaries provide critical habitat and refuge for marine wildlife, serve as important tools in responding to climate change, and prohibit harmful activities including offshore drilling and seabed mining.

One of the most exciting elements of this sanctuary is its Tribal collaborative co-stewardship of marine and cultural heritage. For 40 years, the Northern Chumash Tribal Council has advocated for this marine protected area, to restore the Tribe’s connection to its lands and waters and protect sacred sites along the San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara coast. The Chumash have occupied the central coast for 20,000 years and their deep connection to this area shined through the impressive organizing they carried out to inspire, excited, and motivate over 170 Tribes, congressional representatives, educational institutions and aquaria, and local, state, national and international organizations. It was such an honor to be part of this incredible coalition and witness how successful organizing can be done when it is led by the original stewards of the lands and waters.

Moving forward this sanctuary will be co-stewarded by NOAA and Tribal and Indigenous members to ensure that traditional practices and knowledge are integrated with federal processes. The involvement of Tribal and Indigenous members will ensure that the various Chumash Sacred sites, such as Point Conception and offshore sites along Point Sal, will be protected by those that have generational connections to these sites. This will set a strong precedent for future sanctuaries led by Tribes and Indigenous communities and will be a critical learning opportunity that can facilitate a transfer of knowledge and establish new ways to approach environmental protection and conservation.

The Central Coast is filled with a rich diversity of seabirds, fish, and marine mammals. From the dreamy kelp forest to the deep blue open waters, this area is a biodiversity hotspot. This designation is particularly important as it supports the threatened Western Snowy Plover, 60 percent of the California Brown Pelican population, and significant number of Brandt’s Cormorants and Pink-footed Shearwaters. These species depend on the health and function of these coastal waters, and with the implementation of the sanctuary, we are ensuring their protection for generations to come.

The sanctuary’s boundaries exclude areas where future subsea cables and floating offshore substations could be installed to connect Morro Bay Wind Energy Area to the power grid at Morro Bay and Diablo Canyon Power Plant. While this reduced the boundary size that the Northern Chumash Tribal Council originally proposed, the Tribe worked with the offshore wind developers to secure a phased approach and expand the boundary once the subsea cables have been laid. Phase 2 will commence by 2032, and the process to expand the Sanctuary back to its original boundary would begin.

Sooty Shearwaters migrate an impressive 40,000 miles each year and rely on the open waters of the Sanctuary for food during their long voyage. During my pelagic boat trip, I was in awe of this inspiring bird and wondered what its journey looked like to get to where it was now. I also couldn’t help but be in awe of the community-driven effort that led to the creation of the sanctuary and the journey communities went through to get to this historic moment. This victory proves that through collective care and action, we can support Tribal and Indigenous leaders to move us forward and pave the way to what conservation can look like from the original stewards of the land and waters. Together, we can make positive change—from protecting the ancestral waters of several Tribes along the Central Coast to species like the mighty Sooty Shearwater.