Article authored by Andrea Jones, Director of Bird Conservation at Audubon California, and Joanna Wu, Avian Ecologist at National Audubon Society.

Megafire: The new normal

“We’re having to confront the reality that large wildfires, and the destruction that comes with them, are going to be a bigger part of our future here in California,” says Andrea Jones, Audubon California’s Director of Bird Conservation.

Hers is not a controversial opinion. This year is already California’s worst year on record with regard to wildfires – beating out the past several years, which few thought we would ever top. More than a million acres burned across the state in 2017. This year, according to CalFire, as of August 30th, almost 3.1 million acres have burned, toppling previous years and a 5-year average of 310,000 acres. And we are not even close to done with fire season – there are still several months to go.

California is in uncharted territory with its fires, which are becoming more numerous, more frequent, more widespread, and more intense, with many started by human causes. These megafires are having severe impacts on communities throughout California and the West, and pose a new stressor to California’s birds, which are already threatened by habitat loss, climate change, pollution, and other factors.

It is important to note here that wildfires are a natural and healthy part of California's forest, shrubland, woodland, and grassland ecosystems. Fires cycle nutrients and allow natural areas to regenerate properly. Giant sequoias need fire to crack their seed cones and germinate, and many large redwoods remain standing after the Santa Cruz fires.

Birds and other wildlife have adapted to a natural fire regime over millenia, and their populations will not be negatively affected by them under normal circumstances; in fact, studies show that forests with a diversity of burns (i.e., low, mixed, and high severity) may have higher numbers of bird species after a burn. Birds such as the Black-backed Woodpecker, which are found in California’s Sierra forests, are known to move into severely burned areas to forage on dead trees. Fires can create snags (dead standing trees) that the California-endangered Great Gray Owl, Spotted Owl, and other large birds nest in.

Experts have pointed to a myriad of reasons for the increased number and destructiveness of California wildfires: higher temperatures and prolonged drought are leading to greater amounts of dry, fire-prone forests and grassland. All it takes is a spark, which can come in the form of lightning as we saw in August in Northern California, a downed electric cable, a campfire, or other sources. The trend has all kinds of ramifications for residents, who are now confronting regular threats to property, if not their lives, from wildfires.

Impact of Fires on Birds

Though it is thought that most birds can escape from areas of dense smoke, according to Joanna Wu, Avian Ecologist at National Audubon Society, wildfires affect birds in a number of ways, many of which aren’t immediately apparent. Research finds that bird lungs may be more susceptible to respiratory distress from smoke, they are generally less active, and they may experience a decline in reproduction during smoke events. Whether the current layer of smoke blanketing much of California and the West is impacting birds ability to migrate or hunt for food is not yet understood, explains Wu.

“At this time of year, when birds have fledged and can fly away, the effect on birds from the fires isn’t immediately obvious but may be present in ways we don’t yet understand” Jones says. “There could be long-term implications to some bird populations.” In New Mexico, biologists have recent witnessed large numbers of dead migratory songbirds and have speculated the cause may be related to fires in the West, leaving birds in a weakened condition for migration.

Most birds, of course, are highly mobile. Even as most birds fly out of forests, shrublands, and grasslands that are aflame, that movement is a stressor as they must then compete with resident birds for limited food and water in new habitat areas. And with fires now burning through huge expanses, habitat refuges may be limited.

Jones noted that the fires are likely having an impact on birds migrating along the Pacific Flyway, as it is migration season for songbirds moving from their forested breeding grounds through California to points south.

“Right now, we are in songbird migration season, so we’re going to be seeing a lot of birds coming south, looking for their usual resting spots, particularly along river corridors, in these burn areas,” she says. “When they find these areas burned, they’ll probably continue on their way in search of reliable habitat, or they’ll just try to make it further south without an important stop to rest and refuel.”

Bird migration, Jones notes, is a series of stops, each of which are vital to a bird’s survival. If we remove these links in the chain, birds will have difficulty completing their journeys.

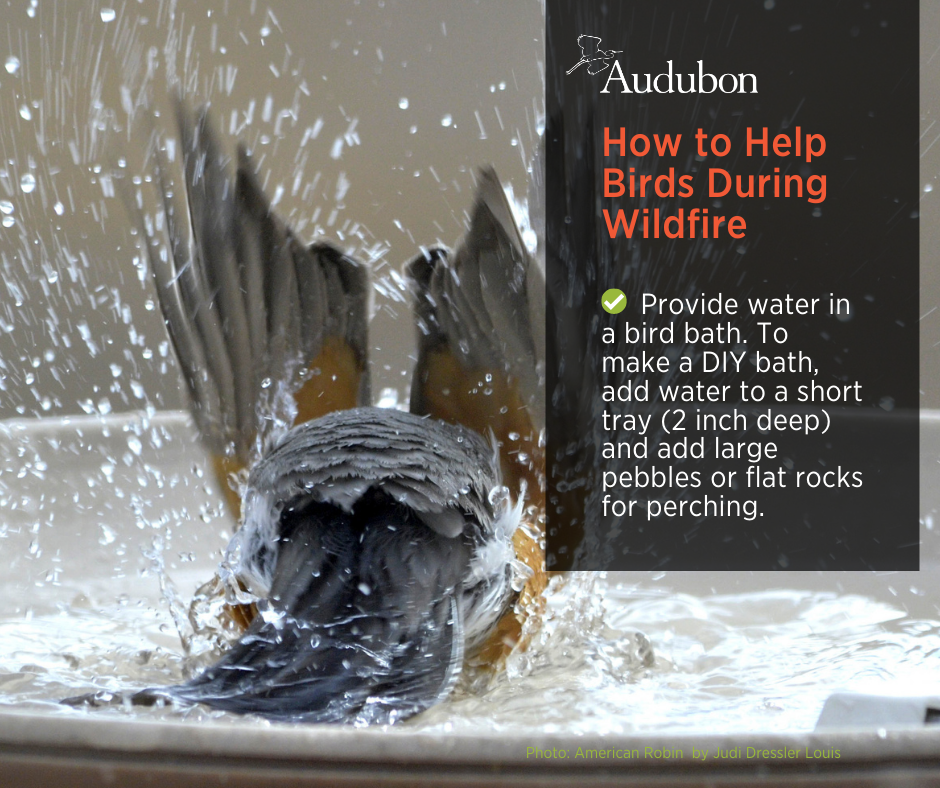

How to Help Birds During Wildfire

Audubon recommends people should put out water sources, such as a bird bath, and bird seed or nectar for hummingbirds during this critical time. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard from people that they never saw a species of bird at their feeders until there was a big fire nearby,” Jones says. “These birds migrating through are going to need some help.”

As we begin to approach the rainy season, it’s a good time to plan for planting plants in backyards and gardens that are native to California, as these are better adapted to drought and fire. Audubon’s Plants for Birds database (https://www.audubon.org/plantsforbirds) can help people find out what plants are appropriate for their area.

Effects of Wildfire on Habitat

Sandy DeSimone is the director of research and education at Audubon’s Starr Ranch Sanctuary in Orange County, and she has studied closely the effects of fire on habitat in Southern California.

“It’s always important to understand that fire is a natural part of almost every California ecosystem, and in many ways is important to its health,” says DeSimone.

DeSimone says that the intense, frequent fires that California has seen in recent years are not normal, and sometimes not healthy for habitat.

“There is research that shows that fires that return after five years or less can change habitat type,” she says. “Studies have shown how frequent fires have converted shrubland landscape into non-native annual grassland. A change to a less supportive habitat could spell a lot of trouble for birds and other wildlife.”

Even in areas where habitat does not convert, it will take a few years for complex layers of habitat to rebuild in California’s burned areas, and as noted above in some cases, what returns may not be what was there before.

“Nesting habitat will be at a premium in the parts of the state that have burned in recent years and this could impact an entire generation of birds in some areas if they are unable to find suitable habitat,” note Jones.

Moving forward

There is widespread agreement that California and other states in the West must improve their forest management efforts to reduce the risks of wildfire. Audubon agrees that the State of California must implement an ambitious program to make the state safer and more fire resilient, but strongly disagrees that State or Federal governments must relax environmental laws or regulations to accomplish these goals.

“The wildfire threats we’re facing today are the result of over a century of poor landscape management in the state, an increase in human development in fire-prone areas, and increasing risks due to climate change.,” says Mike Lynes, Audubon California’s director of public policy. “To reduce risks to people, wildlife, and our economy, the State of California, communities, and stakeholders have to align to better manage our landscapes.

This will require significant public and incentives to private landowners and industry, but it will protect birds, communities, and other wildlife at the same time. We should also be listening to and learning from experienced managers of our ecological resources, including the Indigenous People of California who managed these lands and fire for millennia.”