After 8 years of planning, permitting, surveying, and digging, the Sonoma Creek Enhancement Project has been completed!

Audubon California, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Marin Sonoma Mosquito Control District partnered to enhance 400 acres of tidal marsh habitat on the San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge along Sonoma Creek in northern San Francisco Bay. The project is part of Audubon’s Coastal Resilience work and is the first of its kind to demonstrate how restoration can ensure that the marsh and its wildlife is better adapted to withstand future climate change, particularly from sea level rise and storm surges.

Designated as an Important Bird area, San Pablo Bay and its surrounding wetlands provide critical habitat for the birds of the Pacific Flyway. The project benefits birds such as federally endangered Ridgway’s Rails, state threatened Black Rails, migratory waterbirds, and a number of marsh songbirds, along with the federally endangered salt marsh harvest mouse and native plants. Fish, such as Coho salmon and steelhead, also rely on healthy wetlands as habitat where juvenile fish can feed and grow.

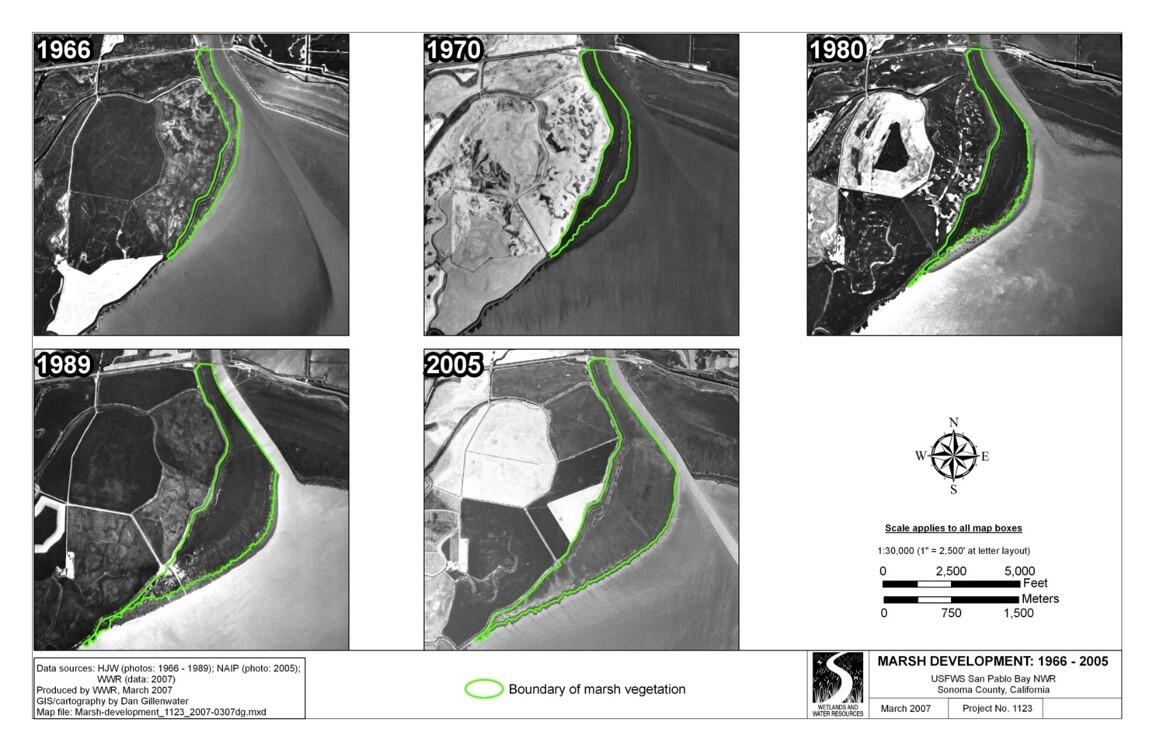

The Sonoma Creek runs from Sonoma County into the San Pablo Bay on the northernmost end of the greater San Francisco Bay. More than a hundred years of mining and agricultural operations have greatly limited the ecological function of these wetlands. Open water sediment from hydraulic mining during the Gold Rush caused a rapid buildup of mud flats which were subsequently turned into farmland, and maintained by levees. Because of these conditions, the Sonoma Creek Marsh is described as “centennial marsh”- one that has formed quickly, on a geological timescale, over the past 100 years.

In the last three decades, tidal action has reclaimed some of area of the marsh and created stagnant wetlands that built up too fast to form natural channels. These stagnant pools form algal mats, harbor mosquitos, and inhibit healthy marsh growth and function. In this image from 2015 you can clearly see patches of stagnant water and dead vegetation.

The core of the Sonoma Creek Enhancement project involved the construction of a network of 5,700 linear feet, or more than a mile, of tidal channels within the marsh to drastically improve tidal exchange and nutrient cycling and provide habitat to a myriad of marsh-dependent wildlife species. The channels also provided spawning and feeding grounds for endangered and commercial fishes.

Improving hydrology improves water quality by increasing circulation and drastically reducing the amount of pesticides applied to areas of ponded water that facilitated heavy mosquito production.

In 2015, after a multi-year permitting process, Phase I construction began! An excavator was brought into the marsh to dig the 30 foot wide, and 7 foot deep channel. Because the marsh was so saturated with ponded water, we had to build a temporary fluid road through the marsh in order to hold the machinery and prevent it from sinkin. At the channel’s connection to Sonoma Creek, the width was expanded to 50 feet!

Material excavated form the channel was used to create mounds of higher elevation ground that would act as upland marsh habitat for native plants and refugia for the endangered salt marsh harvest mouse during extreme high tide events.

Additionally, excavated sediment was used to create a gently-graded high marsh transition zone along the edge of the marsh. The mounds combined with this slope is ideal for reducing storm surge flooding of adjacent private lands and providing crucial high tide refuges for rails, shorebirds, and small mammals.

This project helped pave the way of change for Bay Conservation and Development Commission’s (BCDC) restoration policy and permitting process to make it easier for restoration projects to use dredge spoil for beneficial uses in the future.

As the first phase of the project came to a close, a total of 4,550 feet of channel had been excavated through the center of the marsh. This left 1,150 feet of channel yet to be excavated.

Although there was still work do be done, the stagnant pools in the center of the marsh were starting to drain and a diversity of plants, both naturally recruited and hand-planted, were thriving. New habitat had been created for the endangered salt marsh harvest mouse, the California Ridgway’s Rail, and many other birds, mammals, and invertebrates. Additionally, mosquito populations were trending down due to the reduction in stagnant water.

In October 2020, the final phase of the project began. This time, we were able to secure use of a new amphibious excavator, saving the need to build a road to support the machinery. In this case, the machine “floated” across the surface, causing very minimal damage to the marsh as it worked. It also saved a lot of time and money. One critical aspect of the construction work over the entire course of the project was ensuring that the animals we were trying to save weren’t harmed in the process. Where ever the heavy machinery went in the marsh, biological monitors first had to flush out any potential hiding salt marsh harvest mice. Brooms were used to shake and stir the vegetation, scaring the mice away from the path of the excavator.

When the excavator was in place, work began to finish excavating the final 1,150 feet of channel. Digging began at the tail end, working towards the existing channel, to ensure that the sediment tossed up during digging would not enter waterways.

In addition to extending the main channel and creating mounds excavated sediment, existing tidal marsh channels were extended and enlarged into areas with persistent open water impoundments to improve tidal exchange and drainage, and rock left over from phase one of the project was removed from the channel.

After a rapid 1.5 weeks of construction, the final phase of the Sonoma Creek Enhancement Project was finally completed! The old and new channels have meet to create a continuous 5,700 foot channel through the marsh. Surveys and monitoring will continue into the future to measure the effects this work has had on the marsh and the wildlife that calls it home.

This work would not have been possible without funding and support from:

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service - National Coastal Wetlands Conservation Grant

- California Wildlife Conservation Board

- National Fish and Wildlife Foundation

- California State Coastal Conservancy

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

- Marin-Sonoma Mosquito and Vector Control District

- San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge

- Point Blue Conservation Science - STRAW program (Students and Teachers Restoring a Watershed)

- Individual donors and volunteers