Dark-eyed Junco

Latin: Junco hyemalis

From fires in the Sierra to clouds of windblown dust at the Salton Sea, the effects of drought driven by climate change are impo

Peregrine Falcon Photo: Jim Verhagen

California’s Mediterranean climate has the most variable weather of any U.S. state, so it’s no stranger to catastrophic droughts and disastrous floods. Still, even in a drought-prone region, recent years have been exceptional – the result of natural climate cycles colliding with a warming planet. From fires in the Sierra to clouds of windblown dust at the Salton Sea, the effects of drought driven by climate change are impossible to ignore.

The latest science confirms that climate change has arrived and that we are in the middle of a megadrought. In August 2021, a report by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that climate change is quickening and intensifying. Even in a best-case scenario, global temperatures will likely rise by 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2040.

In May, 2021, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) declared that the nation has entered uncharted territory in which climate effects are more visible, changing faster and becoming more extreme. Temperatures are rising, snow and rainfall patterns are shifting, and more extreme climate events –like heavier rainstorms and record high temperatures –are already happening. Some, like hotter forest fires, are directly related to historic drought conditions gripping the U.S. West.

The consequences for both California’s avian and human populations are likely to be devastating. Simply put, climate change is the number one threat to the survival of our nation’s birds. In 2019, the National Audubon Society released Survival by Degrees, a study examining the impacts of various climate change scenarios on North America’s birds. Under a worst-case rise of 3.0 C, up to two-thirds of bird species face extinction, including from specific factors like extreme heat and fires. The report came on the heels of another by Cornell’s Lab of Ornithology that the continent has already lost an estimated three billion birds since 1970 due to habitat loss and climate change.

Audubon's Bird and Climate Report

Just 200 years ago, the Central Valley was a vast, seasonal wetland teeming with birdlife. Only about five percent of California’s historic wetlands have survived two hundred years of colonization and intensive agriculture. Those that remain are heavily managed, for the most part receiving water allocations from the state water system together with California’s cities and farms. In addition, some agricultural lands, like flooded rice fields, serve as “surrogate wetlands,” providing vital habitat to migrating waterfowl and wading birds.

However, as of August 2021, the state’s largest reservoirs, Lake Shasta and Lake Oroville, were respectively at 35 and 24 percent of capacity, with proportionate impacts on water deliveries to farms, cities, and wildlife refuges in the Central Valley and elsewhere in California. Our last remaining Central Valley wetlands are expected to receive less than 60 percent of their usual water supply. Winter flooded rice fields, which provide half of the winter waterfowl food supply, are expected to be reduced by 75 percent. The importance of keeping water flowing in the Central Valley is difficult to overstate. Tens of millions of birds depend on the area’s rivers and wetlands as they migrate through an otherwise arid region.

Flooded habitat provided by the region’s farms, refuges, and other managed areas supports between 5-7 million waterfowl and 350,000 shorebirds each year. That’s over 60 percent of the total population along the Pacific Flyway and 20 percent of the nation's waterfowl population. Migrating landbirds also rely heavily on Central Valley stopovers; an estimated 65 million birds pass through during fall migration, along with 48 million each spring. Those numbers include a quarter of all North American Tree Swallows and a whopping 80 percent of Lawrence’s Goldfinches.

Years of fire suppression in western forests and California’s years-long drought have created a trifecta of conditions perfect for explosive wildfires: extreme heat, low humidity, and abundant, desiccated vegetation fire needs to spread. In fact, the state’s worst-ever fires, the 2020’s August Complex Fire at more than a million acres and the 2021 Dixie fire, at more than 960,000, both dwarf all previous fires in both size and ferocity.

The increasingly apocalyptic wildfires of the past five years have cost California dozens of lives and billions of dollars, though the toll on birds is somewhat harder to quantify. While most birds can easily escape advancing flames, extensive wildfires across the western United States in 2020 are suspected at least in part for causing a mysterious die-off of migrating birds in the Southwest. Fire can cause birds to migrate to winter habitats before their bodies have stored enough fat for the arduous journey and thick smoke may disorient some and kill others outright.

While western forests – and their birds – evolved with fire as a natural part of the ecosystem, vital in maintaining diverse habitats, no analog exists for the megafires of the past decade. Experts expect that temperatures in the Sierra will rise by some 10 degrees Fahrenheit over the next century and that the snowpack to melt almost a month earlier. By the end of the century, that could double the acreage burned by wildfires each year.

California’s largest lake is located in one of its most arid regions. The Salton Sea formed in 1905 when an irrigation canal from the Colorado River broke and flooded a historic lakebed. The breach was fixed within a few years, but the Salton Sea, fed by agricultural runoff, remained and became a vital stopover for migrating birds that no longer found wetlands available farther north.

But the Sea is evaporating quickly.

Drip irrigation, and the diversion of the water saved to thirsty San Diego, means that not enough water is flowing to the Sea to maintain it. The retreating shoreline has exposed thousands of acres of playa, or dry lake bed, which contains a century’s worth of agricultural fertilizers, pesticides, heavy metals, and salts. Those contaminants, blown airborne by desert winds, waft towards surrounding towns as choking dust, causing high rates of respiratory illness in some of California’s most disadvantaged communities. Meanwhile, as the surface area of the lake decreases, its salinity increases, killing the fish on which many species of migratory birds depend.

While limited restoration work on the Salton Sea is beginning to proceed – after years of delays – the Sea’s future in a warming climate remains very much in question. Audubon is working with the state of California and partner organizations to maintain the Sea as an asset both for wildlife and for surrounding communities.

While there’s no denying the gravity of the climate crisis, it’s not too late to limit warming and stave off the worst impacts of climate change. With rapid action, we can still limit warming to 1.5 degrees and push lawmakers to enact water policy good for both humans and birds as we all adapt to this warmer, drier new normal.

Audubon and our many partners are working to complete science to better understand how drought impacts birds, we are working with land managers to roll out emergency drought relief funding to create bird habitat, and we are advocating for long-term policy and infrastructure solutions that will make California, our communities and our birds more resilient to this new climate reality.

We are in uncharted territory. Birds are on the move to escape the smoke and stress. What will happen to them and the habitat they need to survive?

Vital protections are needed for wetlands that depend on groundwater under the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act

Audubon science finds that two-thirds of North American birds are at risk of extinction from climate change.

Audubon California has begun the planning phase for the restoration and enhancement of the newly emerging Bombay Beach Wetland, located by the town of Bombay Beach at the Salton Sea.

Funding to address threat to 1.6 million people and 300 species of birds

More than 400 species of birds come to the Salton Sea in California.

Conservation groups including Audubon California hope that more than $80 million included in the recently-approved state budget will be the first step in a longer, more substantial commitment from the Legislature to addressing the developing environmental crisis at the Salton Sea. The $80.5 million for planning and restoration at the Salton Sea, part of the $167 billion state budget, will ultimately come from Proposition 1 funds approved by voters in 2014.

While the new funding marks the largest amount that the State of California has ever contributed to restoration at the Salton Sea, it is nonetheless only a fraction of the several billion dollars that will be needed to stabilize the situation there.

The funding will help the state pay for the development of a long-term management plan that seeks to address the problems created by reduced water deliveries to California’s largest inland lake. As the Salton Sea shrinks in the coming years, it is expected to have serious ramifications for the more the 400 species of birds that rely on its habitat. Less water will also result in the exposure of hundreds of acres of plays, creating a toxic dust and a serious public health hazard.

Money will also jump-start restoration of habitat along the edge of the lake, creating infrastructure to move water to a number of habitat areas.

An independent California oversight agency last week called on California Gov. Jerry Brown to declare a state of emergency to resolve the environmental disaster unfolding at the Salton Sea. In a strongly-worded letter, the state’s Little Hoover Commission shared the results of recent hearings, arguing that the Salton Sea should be given as high a priority as high speed rail, the twin tunnels, reduced carbon emissions, and increased renewable energy.

The Commission is responding to the upcoming implementation of water diversions from the Salton Sea that will eventually result in 40 percent less water filling the state’s largest inland lake. This will have a devastating impact on bird habitat and expose huge swaths of lakebed, potentially creating dust that will present a serious public health threat to the 650,000 Imperial County residents nearby.

Audubon California is particularly concerned about the situation at the Salton Sea because of the regions particularly high value to birds. More than 400 species use the Salton Sea, many of which are threatened or endangered species.

“Unlike a wildfire burning out of control or an oil spill blackening beaches, the Salton Sea disaster is slowly unfolding, and has been all but ignored until recently,” the letter reads. “When other disasters destroy California lives and livelihoods, Governors declare a state of emergency. The looming Salton Sea disaster warrants the same level of urgency.”

The commission offered four specific recommendations to get the state’s response to this crisis moving.

Madrone Audubon Society are involved with a phenology program designed by Sandy DeSimone of Starr Ranch Sanctuary. Their local paper, The Petaluma Argus Courier, recently intervied chapter members about the volunteer program.

Beginning last month, a group of 10 volunteers armed with clipboards, binoculars and data sheets began to observe the changes and behaviors of a handful of plants and birds as well as an animal at Paula Lane Open Space Preserve, logging their findings into the USA National Phenology Network “Nature’s Notebook” database, which gives scientists access to aggregated data from participants around the nation to inform their research.

A team of about five volunteers is also undergoing monthly observations of the migratory cliff swallow population that makes its home each year at the Petaluma River Bridge from March until August, according to Susan Kirks, a Petaluma resident who’s spearheading the local efforts sponsored by the Santa Rosa-based Madrone Audubon Society...

As part of the project that kicked off the week of May 16, trained volunteers spend about an hour and a half at the preserve once a month to record observations on nine bird species — including several that have been identified by the National Audubon Society as being threatened by climate change — as well as four native and non-native plant species, while also tracking the behavior of the mule deer that populate the land, Kirks said.

Read the rest of the article here.

A picture says a thousand words, as the saying goes. The above postcard from the 1950s shows a bustling Salton Sea Marina, a center of fun and recreation.San Bernardino Valley Audubon's Drew Feldman recently visited the exact same location and took the photo below, which shows just how much things have changed over the years.

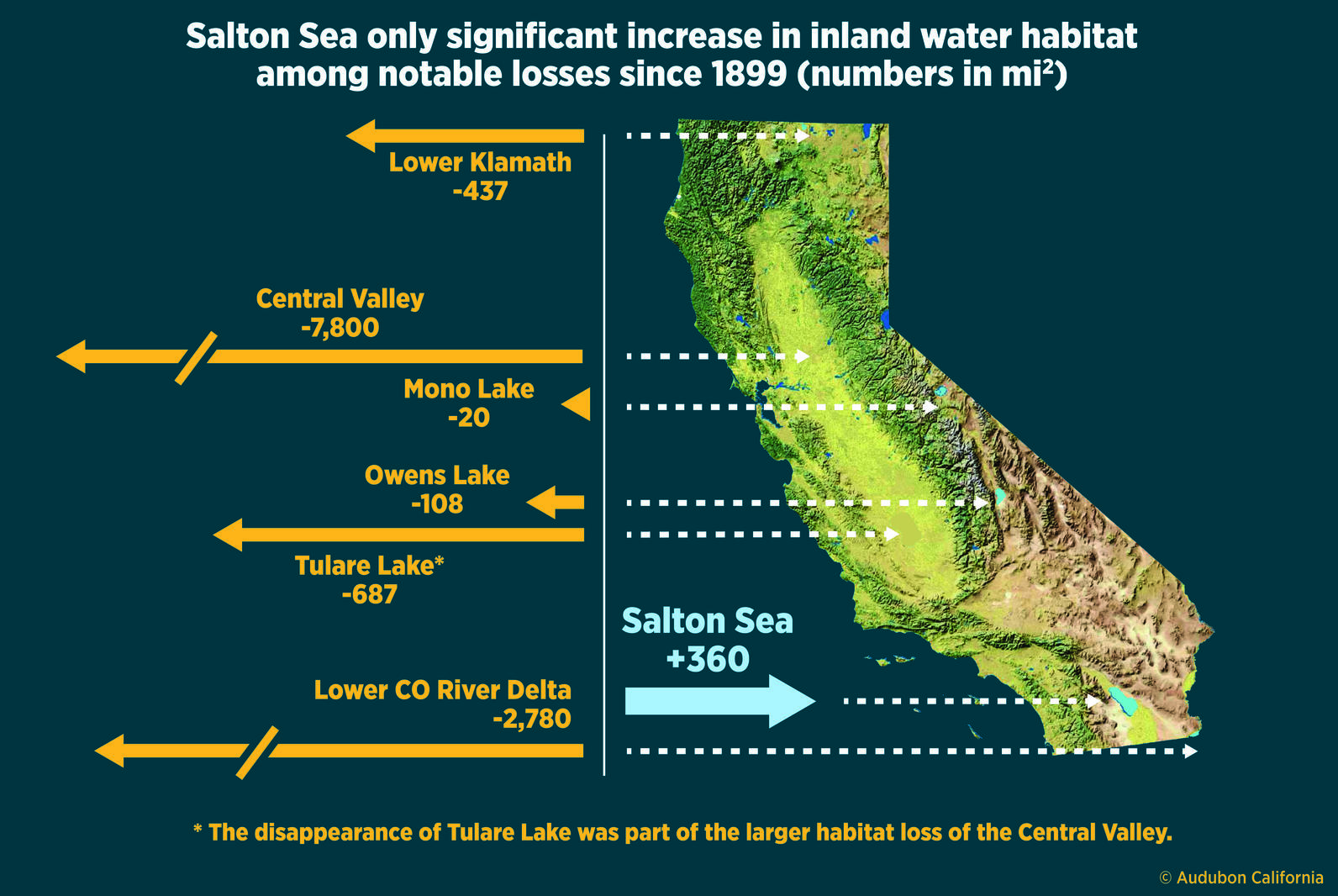

Audubon California Executive Director Brigid McCormack today writes in the Desert Sun that while the narrative around the Salton Sea is often one of environmental decay, the site remains one of the most important places for birds on the Pacific Flyway. She notes that it was created at a time when humans were wiping out natural inland water habitat:

"For birds, the creation of the Salton Sea came at just the right time – just as humans began wiping out wetland habitat throughout California.

Two years before dredging began on the Imperial Valley canal, the last remnants of Tulare Lake disappeared. Once the largest freshwater lake in the West, Tulare Lake was nearly twice the size of the Salton Sea, and anchored more than five million acres of Central Valley wetlands, 95 percent of which are now gone.

In 1906, the federal government began work on the Klamath Project, which eventually eliminated 437 square miles (80 percent) of wetland habitat in the Klamath Basin along the California/Oregon border.

Just a few years later, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power began diverting water from the 108-square-mile Owens Lake, where Native Americans recalled a sky blackened with migratory birds, and naturalist Joseph Grinnell found great numbers of avocets, phalaropes and ducks. By 1926, Owens Lake was gone.

Fascinating piece today in the Los Angeles Times about the growing concern over declining water levels in Lake Mead that, if they continue to fall, could trigger substantial water cuts in Arizona and New Mexico. Because of this pressure is growing on California users to reduce its use of Colorado River Water. You might recall recently that the Imperial Irrigation District, one of the primary users of water from the Colorado River, has said that will be uncomfortable with any agreement regarding Colorado River water unless the major issues of habitat conservation and dust mitigation at the Salton Sea are resolved.

"All the parties are under pressure to reach an agreement by the end of this year, before the current administration leaves office and the process has to start anew with new federal overseers. But the interstate complexities may pale in comparison with the difficulty of working out agreements among water users within each state. California's Imperial Irrigation District, which has the largest entitlement of Colorado River water, has balked at any agreement to preserve water levels in Lake Mead without a parallel agreement to preserve the Salton Sea. That huge inland pond has suffered as a result of earlier multi-billion-dollar deals by which the Imperial Irrigation District transferred water to San Diego, the MWD and other users.

The shrinkage of the sea already is an environmental and public health disaster. Withholding more water in Lake Mead without a rescue plan would be unacceptable, Imperial Irrigation District General Manager Kevin Kelley said recently. "The Salton Sea has always been the elephant in the room in these talks," he told the Desert Sun newspaper."

When Audubon California talks about the Salton Sea, we often highlight that about 400 species of birds make regular use of this habitat -- massive numbers of sandpipers migrating between Alaska and South America, as much as 90 percent of the world’s Eared Grebes, and large numbers of American White Pelicans, Double-crested Cormorants, the threatened Snowy Plover. Without the Salton Sea, these species and many others would struggle for survival.

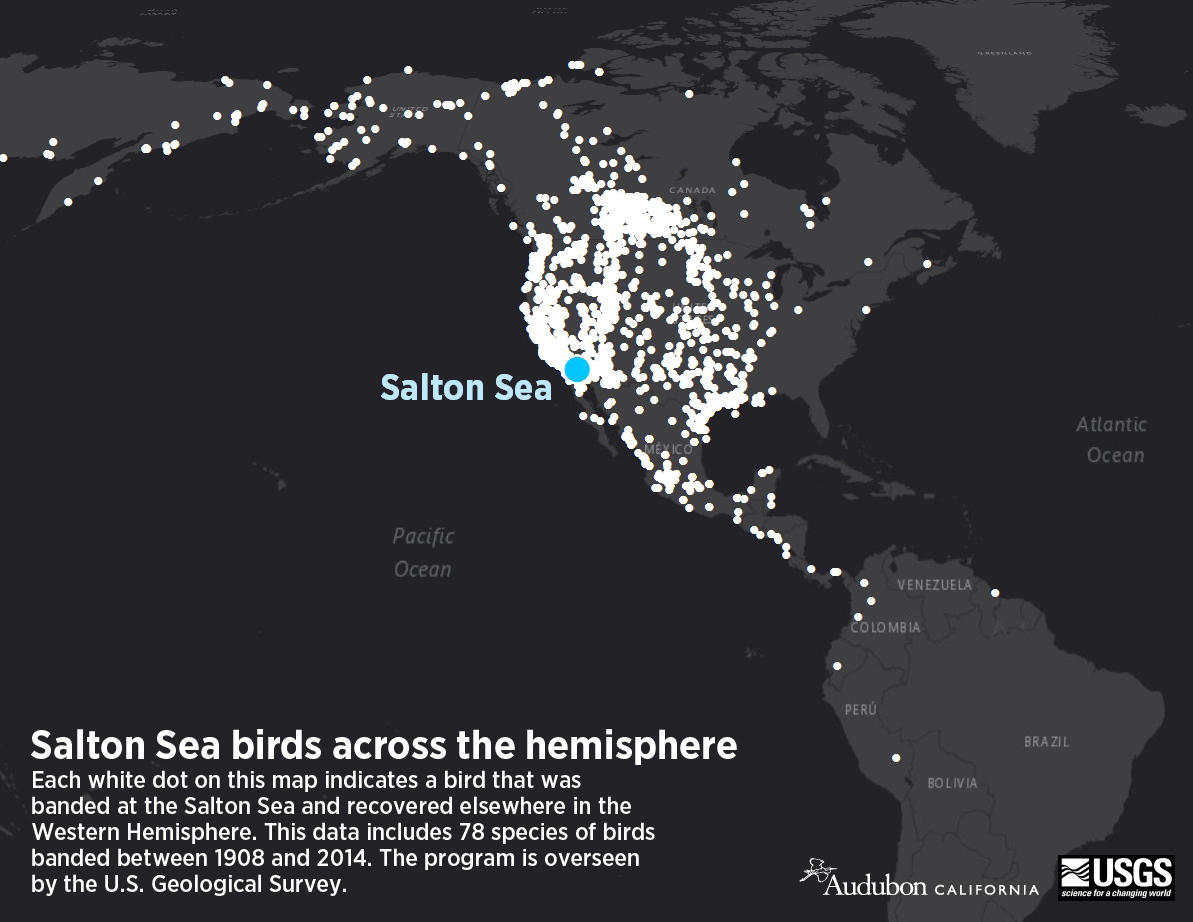

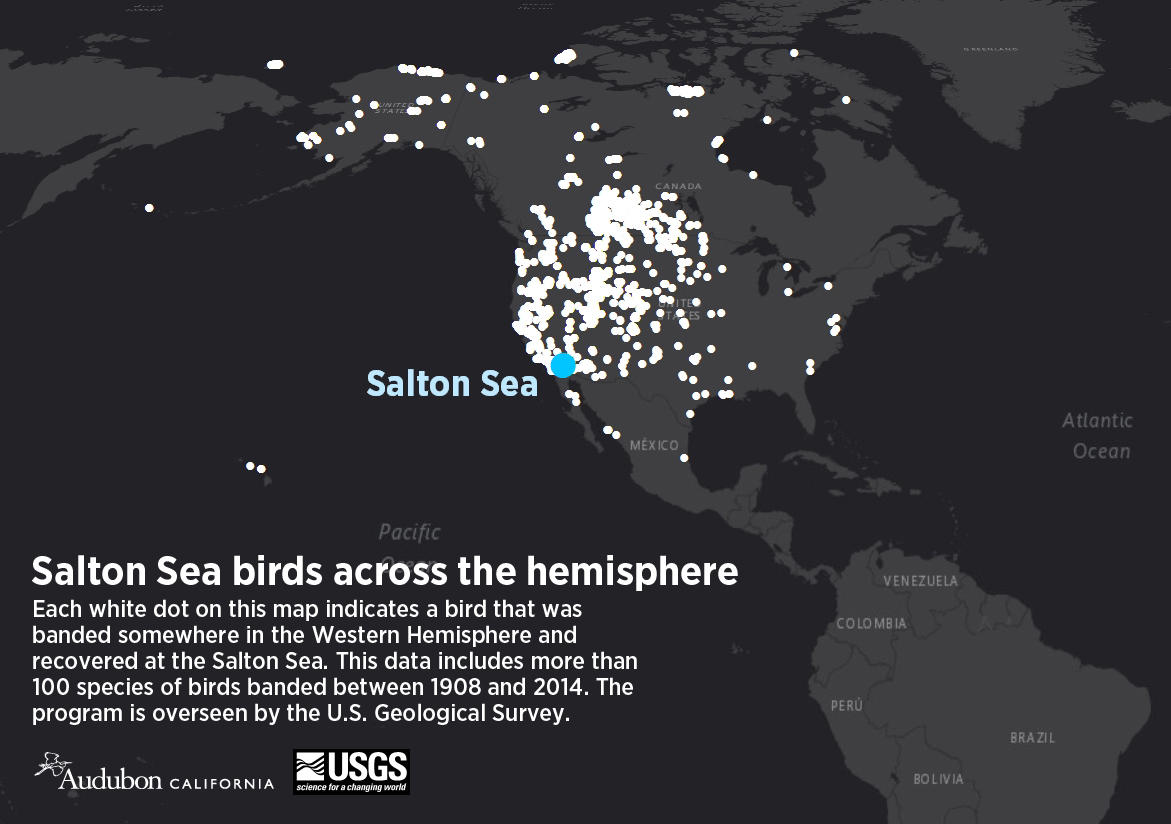

The two maps below offer another view of how birds from all over the Western Hemisphere use the Salton Sea. Since 1908, volunteers and researchers have been banding birds for the U.S. Geological Survey's North American Bird Banding Program, and so we have data on where we found birds that were banded at the Salton Sea, as well as where birds were banded that ultimately turned up at the Salton Sea.

Birds banded at the Salton Sea and found elsewhere

Birds banded throughout the Western Hemisphere and found at the Salton Sea

Our newsletter is fun way to get our latest stories and important conservation updates from across the state.

Help secure the future for birds at risk from climate change, habitat loss and other threats. Your support will power our science, education, advocacy and on-the-ground conservation efforts.

Join the thousands of Californians that support the proposed Chuckwalla National Monument.

Our newsletter is fun way to get our latest stories and important conservation updates from across the state.

Help secure the future for birds at risk from climate change, habitat loss and other threats. Your support will power our science, education, advocacy and on-the-ground conservation efforts.

Join the thousands of Californians that support the proposed Chuckwalla National Monument.