“Rails are everywhere!” exclaimed Meg Marriott, biologist at San Pablo National Wildlife Refuge, as we carefully walked along the levee next to where Sonoma Creek empties into San Pablo Bay. It had been one year since Audubon, in partnership with the refuge and Marin Sonoma Mosquito Control District, completed the 400-acre Sonoma Creek Marsh Enhancement Project. To celebrate this milestone, Audubon staff and board headed out to the refuge in October, accompanied by Meg, to check out conditions there.

To our delight, we found that the marsh is recovering. With more than 1.5 miles of channels now dug through the marsh, it drains properly with each tide as a marsh should, flooding and draining with the tide.

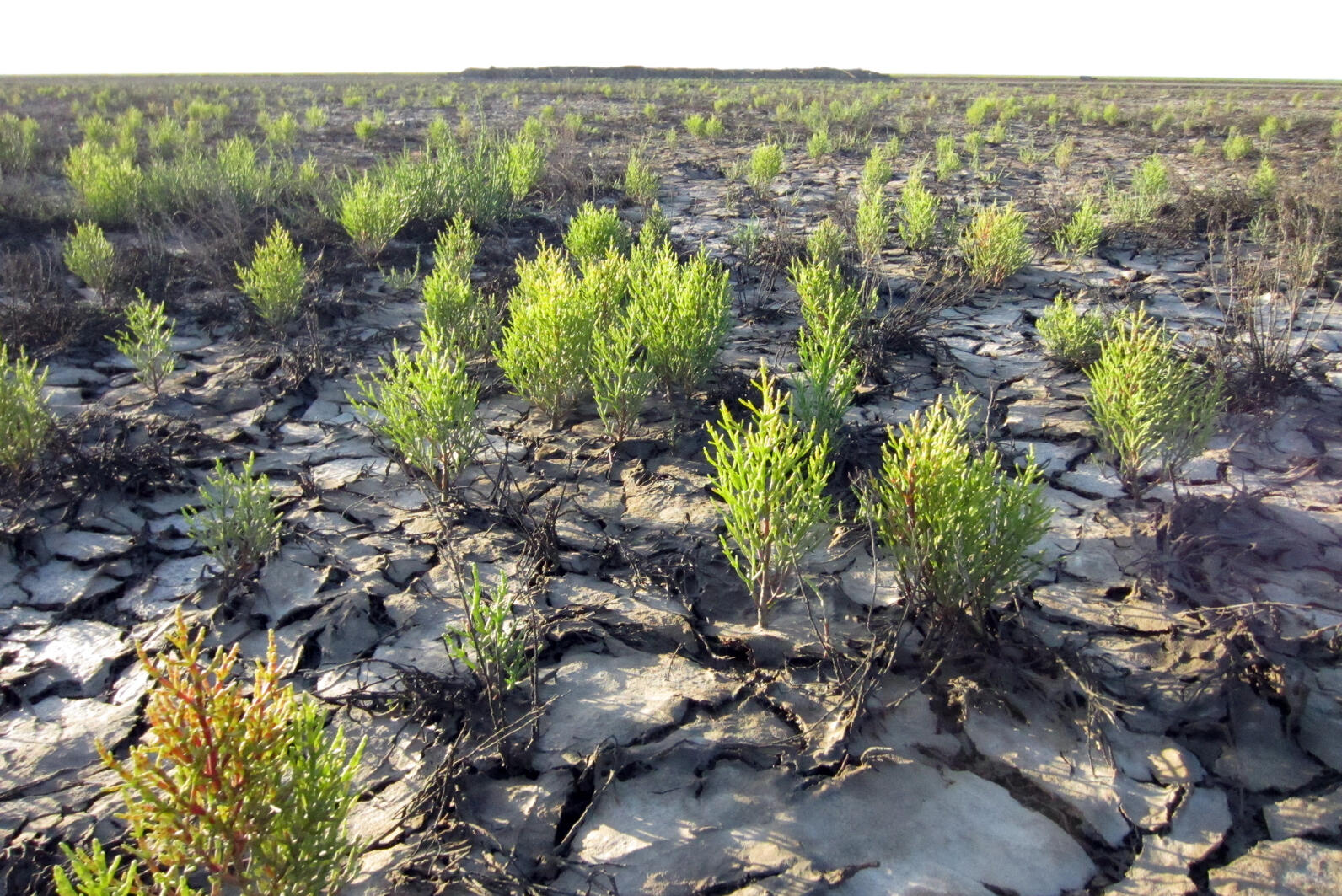

The pickleweed (Salicornia) should be the predominant plant of these tidal wetlands. However, in this marsh, before our project started eight years ago, the central basin was devoid of plant life because of flooding and ponding, without adequate drainage. The stagnant water prevented plant life but did not prevent the production of clouds of mosquitos.

Mosquito production is now dramatically reduced, but Rail production is dramatically increased. Both federally endangered Ridgway’s Rail and state endangered Black Rails breed here, sharing their homes with the federally Endangered Salt Marsh Harvest Mouse. All are rebounding because their home is no longer getting flooded and the dead stagnant pools are replaced with fresh pickleweed, meaning there is now more nesting habitat for these rare animals.

Sonoma Creek Marsh

We know that sea level rise and more severe storm events are going to hit the San Francisco Bay area. These animals have a hard time getting out of the way of floods, pickleweed or no pickleweed. That is why we created marsh mounds, slightly elevated areas predicted to stay above water in the most extreme of king tides or storms. We also created an upland transition zone – a gently sloped barely discernable ramp that leads from the marsh towards the human-built levee. We constructed this ramp using mud that was excavated on-site from the channels we dug, and then with the help of Point Blue Conservation Science’s STRAW program, the area was planted with native plants.

It was amazing to see how the area has filled in completely with native plants from bare mud and is now providing a safe haven for rails and mice to seek shelter from the high water among these plants.

Our staff biologists Paige Fernandez and Haymar Lim, and Restoration Expert Dan Gillenwater, continue to visit the marsh and monitor the conditions to learn if our experiment was successful in creating a resilient marsh. And Meg continues to count great numbers of rails. Our early indications suggest that it did! Sonoma Creek marsh is now a “climate stronghold”, a safe place for rails and mice, other birds and fish to survive. Without marshes like this one, the future of these rare species would be bleak.