At Audubon California, we support wildlife-smart development of solar energy and other renewables in order to mitigate climate threats to birds and other animals. However, there are still a few problems left to quack when it comes to solar energy—and one of those issues is the so-called duck curve.

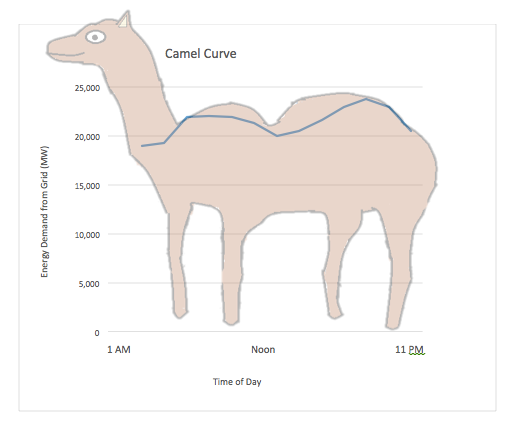

We can find the duck curve when looking at a graph of an area’s demand for electricity from the power grid over the course of a typical day. But first, it’s important to look at what our demand on the grid looks like without renewables. This “traditional” electricity demand is said to look like a camel, with two humps in the curve during times with the most electricity usage (in the late morning and in the evening).

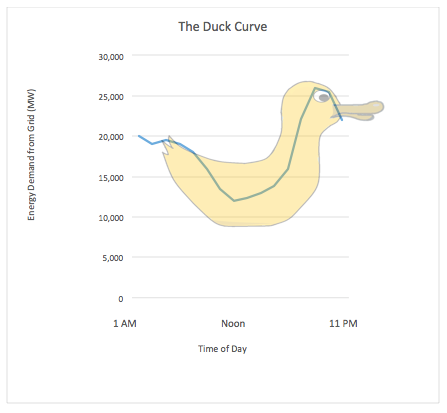

By contrast, the duck curve shows how solar power provides extra energy and thus relieves some of the demand on the grid. Solar power is strongest during the day, so this extra electricity takes away the first “hump” of the camel and instead forms the “belly” of the duck around noon when less power is needed from the grid.

While this might seem like a good thing, some worry that if there is more solar than demanded electricity, the grid will become overwhelmed. While this has yet to happen in California, there is concern that the transition between having plenty of electricity when solar power is active and needing substantially more energy when the sun goes down may occur too quickly. Why does this matter?

In order to sustain a baseline power, our energy system has traditionally been supplied by a coal or nuclear plant. Other power plants—typically natural gas—are turned on when there is more demand. In the past, these humps have always been gradual enough to allow utilities to turn on and off the necessary power sources. Now, the fear is that there won’t be enough time to flip extra power sources on and off in the steep rise of demand. This takes the form of the duck’s neck in the graph. Even if we do have enough time to switch from solar to other energy sources, the increased number of switches could be inefficient and reliant on less-green forms of energy such as natural gas.

There is some debate over how bad the duck curve will get, and whether or not the problem is exaggerated. According to Garry George, Director of Renewable Energy for Audubon California, handling the duck curve is an important part of moving to a carbon-free grid. “Managing the duck curve is still one of our obstacles to achieving 50% renewable energy by 2030,” George said. “There is a significant amount of research being done on managing the grid through storage, and we expect this will continue.”

Our hope? That the research and pilot programs go swimmingly, so that the ducks stay in our ponds and off of our electricity charts.

By Ada Statler-Throckmorton

Monthly Giving

Our monthly giving program offers the peace of mind that you’re doing your part every day.