It was mid-June and the sun was just coming up. It was already around 80° F at 5:30 am as we walked onto the Salton Sea playa, the exposed lakebed that has been rapidly increasing since 2017 as the water in the Sea recedes. As we work our way through the invasive Tamarisk trees and around the Iodine bush and Saltbush on the upper playa, the morning silence is broken by the calls of Black-necked Stilts. Rounding a corner, a wetland opens up with pools of water and tall cattails all around. The Black-necked Stilts and American Avocets are walking around in the pools of water feeding, while others fly over our heads making calls. Our excitement peaks as we stand and take in this beautiful morning scene of native wetland habitat with birds thriving in it. This is what we were hoping to find.

The Salton Sea is still a hot spot for birds. Wetlands support marsh birds, while the shallow waters of the Sea and in the wetlands support hundreds of thousands of migratory waterbirds and resident bird populations. The upland habitats too support songbirds and raptors. Although this place is changing and threatened, it remains an important stronghold and reliable stopover for migrating birds as other stopover wetland sites become scarcer.

On this trip, we are exploring and documenting new emerging habitats at the Salton Sea. The agricultural drains, seasonal and perennial streams, and washes that used to run directly into the Salton Sea now spill out onto the exposed playa, creating new wetland habitats for birds, fish, and other wildlife. These wetlands also control harmful dust emissions from the playa that contribute to poor air quality and health issues, and can be key to improving public health in local communities. And these emerging areas of greenery and wildlife may at some point contribute to the thriving regional ecotourism seen in the desert regions around the Sea.

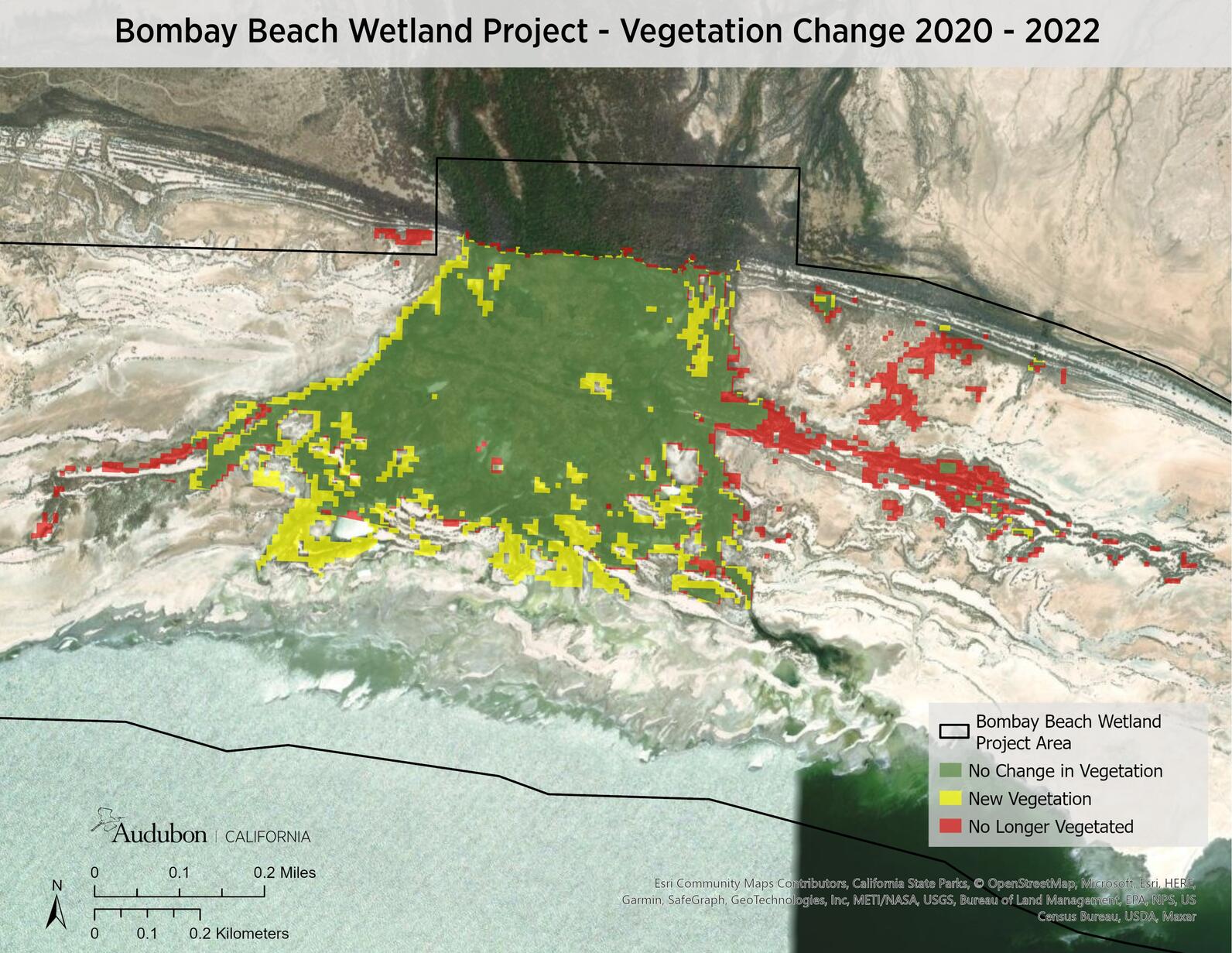

We’ve been studying the emergence and persistence of these new habitats with satellite imagery since 2019, but not much is known about the relative quantities of native vegetation versus invasive Tamarisk that make up these vegetated areas on exposed playa. One reason is they are difficult to access and much of the native habitat seems to be surrounded by nearly impenetrable stands of Tamarisk.

Later in the morning temperatures had just gone over 100 ° F but it felt much hotter as we walked across the white-salt-crusted playa. As we watched a few Snowy Plovers run around near a pool of water, we discussed the differences between the types of vegetation and what they provide for birds. We know that the Tamarisk provides habitat for songbirds or landbirds, while the native wetland vegetation and shallow water areas provide habitat for marsh birds, shorebirds, and waterfowl.

We decided to record a bit of audio to see what birds were using which habitats. As we slipped into a dense stand of Tamarisk, we opened the Merlin Bird ID app on a phone and began to record the bird calls ringing out all around us. The app will identify birds based on their calls, and we recorded over a dozen, all songbirds. We heard Song Sparrows, Common Yellowthroats, Black-tailed Gnatcatchers, Western Meadowlarks, and Verdins, to name a few. When we repeated this in a native wetland area made up of open and shallow water pools and cattails, we found a very different assemblage of birds, including Least Bitterns, Common Gallinules, Marsh Wrens, Black-necked Stilts, Western Grebes, Caspian Terns and the list goes on. We unfortunately did not capture the call of the endangered Yuma Ridgway’s Rail, but we do know that it is found in these areas at the Salton Sea and is dependent on these native wetland habitats.

Understanding these emerging habitats is critical because California has already lost about 95% of its native wetlands. The little remaining wetlands continue to disappear as water grows scarce and land uses change. These new wetlands forming at the Salton Sea are no different, as most are supported by runoff from agricultural drains. As water restrictions tighten and farm irrigation becomes more efficient, less water will reach these wetlands and they could disappear.

Tamarisk itself can also be a problem: invasive and out-competing native vegetation, it uses more water than native vegetation and slows water movement so that it can percolate into sediments instead of flowing through to provide water for native habitats downstream. So, it’s important for us to know how much of these new vegetated areas are made up of what types of plant species.

We continued our surveys for several days. We explored emerging vegetated areas and wetlands all around the Sea. At times the Tamarisk was too dense to enter more than a dozen yards or so, despite pushing hard through the dense bushes and trees. In other places, we wrestled through Tamarisk stands and found native wetland plants, or drove up to the edge of where the Sea once was to find native wetlands there providing habitats for waterbirds. We explored more than 20 different sites, photographing, and mapping vegetation and noting differences between habitats. Although it was very hot, we enjoyed desert sunrises, cooling date shakes at the end of the day, exploring these remarkable emerging habitats, and the peace of watching and listening to an amazing assemblage of birds.

After completing our surveys, we took our data back to the office, tired and thirsty, but with a renewed appreciation for this unique landscape. These data will be incorporated with drone mapping and satellite imagery to create vegetation models to tell us what these wetlands look like, including type and relative quantities of vegetation. We hope to better understand how these wetlands change and what types of vegetation are in these important and emerging habitats. We’re also collaborating with local community science groups studying water quality in these sites, to analyze how the wetlands may impact the water that flows through them.

This information can be used to better understand how much water may be needed to support these critical habitats at the Salton Sea and help us continue to advocate for protecting and enhancing these areas. Even now, we can see these rare wetlands hold so much potential value for communities at the Salton Sea, alongside the hundreds of thousands of migratory birds that depend on this special place.